Just how do 3D printing and craft fit together? Is it just a matter of using a virtual image or scanning in what you want and shoving a copy of that thing out of the printer? Or as many copies as you want out of the printer?

And how is that craft?

Igor Knezevic – 3D printed lampshade – www.alienology.com

{click image for link}

Firstly, it’s important to understand that there are several different types of 3D printing. Early versions used to shoot precise laser beams through a plastic soup, and where the beam struck, the soup hardened. Most commonly now, there is Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) which works kind of like an ordinary inkjet printer, spitting out a string of plastic (or metal etc), building the image up in layers (these are the type of machines made by Makerbot and Filabot). A newer type is Selective Laser Melting (SLM), and builds on original ideas, using a high-powered laser beam to fuse together finely powdered metal.

The very biggest advantage of any of these types of printing is that as long as you can put the design on screen, you can print it out. Infinite flexibility. (Almost.)

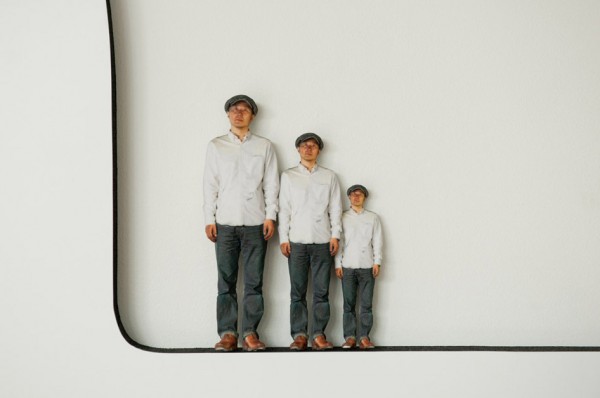

{omote 3D was a pop-up event last year in Japan that involved scanning members of the public in a special booth and printing them out in full colour. There were even family portraits.}

There are, however, some serious drawbacks to 3d printing.

1. you can steal designs. Would you like your own Eames chair rip-off? How about some new Lego? And … how about that cute new iphone cover you just saw on Etsy? Breach of copyright is not only dishonest, for small businesses it can be downright devastating. (More of my thoughts on copyright in the digital age here.)

2. technology grows old quickly. Just like the increasing number of old phones and old computers, there will be an increasing number of obsolete printers, discarded in favour of cleaner, faster, more flexible machines. What do we do with old tech? We already have an uneasy relationship with our growing mountain of tech waste. Out of sight out of mind is no solution at all.

3. more waste. You can’t recycle your unwanted creations easily. What do you do with all those ugly bits of plastic experiment and bad prints that you can’t use/don’t want? Filabot do make a machine to reclaim some plastics – but that’s an extra piece of equipment with extra maintenance and extra expense, which is also subject to becoming outdated in the future.

But of course, when the technology is used properly, there are excellent advantages.

1. less waste. Despite the production of unwanted objects that may be difficult to recycle, overall there is less waste during the manufacturing process – think of all the scrap material discarded when cutting, drilling, filing and sanding in more traditional making processes. With additive printing, you only really use as much material as you need.

2. you don’t have to make new moulds for every new product that you try. You use no moulds at all.

3. you get exactly what you want. Especially useful when you can’t find what you want in the shops. Can’t find that rare spare part for your dooverlacky? Print it out. Got a great idea for a new aerodynamic handbag so you can glide through the shops? Print it out. You can design your product and see it on screen, tweak it and put it through 100s of iterations before deciding to manufacture, instead of building possibly hundreds of test pieces to discard before the final design. In many instances, the physical properties could also be tested virtually, before discovering problems during the manufacturing process.

So, back to the question of craft. Does 3D manufacturing replace, shift or enhance traditional methods?

Perhaps, because most of us have not had personal experience with this technology, we might be forgiven for thinking that a maker working in a virtual environment has perfect control over their material. However, consider the growing number of different materials that can be used – this requires a working knowledge of each material’s particular behavioural properties. Then there’s post-processing which is totally hands-on – there are many finishing processes used, such as removing supports, smoothing and sanding, painting, dyeing, polishing, joining and more.

Renowned portraitist Chuck Close utilised digital technology to create a series of loomed tapestry self portraits. They took Close around a year to set up before printing – selecting palettes, running test strips, calibrating. He considers that there is an enormous amount of labour still involved – but that it shifts in focus from the end to the beginning of the project.

In a post on the Facebook Group Critical Craft Forum, the question of 3D printing and craft came up. In the discussion, Kevin Murray reminded us of the furore that photography caused in painting circles when it first became popular in the 1800s. But photography did not replace painting despite the fact that they both produced images. Instead, the new technology helped to push painting in new and exciting directions. He continued; “To say that tool developments are interconnected is not to deprive the artist of any freedoms, but to offer the possibility that new creative practices are opened up in the wake of technological ‘advances’.”(1)

New things! A space for possibilities.

Experimentation is part of the conversation. Take this very cute bear – it’s a traditional stop frame animation, using 50 small 3D printed bears, made by creative agency DBLG, based in London. And it’s beautiful.

In the same discussion on Critical Craft Forum, another group member Rachel said “It is interesting to see how many people have negative feelings towards 3D processes. Implying that when using those processes, you are not using your brain only shows a lack of understanding about the tools and media available. All craft, 3D printed objects included, require creativity, intelligence, I hope originality, and most certainly skill.”

“I think the problem is the mainstream idea that makers using 3D processes are simply scanning objects and shoving them out to the printer. This is just wrong. What you’re seeing are examples of how “cool” the new technology is on the surface, not what it can do when a skilled maker is behind the tools.”

“Junk can be made with traditional processes and junk can be made with new processes.”

“Just as photography did not replace painting, 3D processes do not replace traditional processes. All are valid mediums of making. Objects created are deemed successful or unsuccessful due to the skill, efforts, and creativity of the maker, not the tools or medium. Rejecting a medium or set of tools because it is not what you would prefer to use, or you don’t understand them, doesn’t move anyone or any field forward.”

At the intersection of digital and handmade, artists are exploring ways of how to include the human touch using digital tools.

One has constructed an environment where a gluegun-type pen is wielded freehand, but where it intersects with the projected virtual computer model, the holder of the pen experiences resistance so that they know where the model should be made; however they still have the freedom to express their craft knowledge as well as be inclusive of the natural imperfections of the handmade object.

Design collaborative Unfold have produced technology that scans your moving hands, and so allows you to shape your form in the air while you see it on screen, becoming like a virtual potter’s wheel.

Architectural and film concept designer Igor Knezevic gets me thinking on a whole different level. ” I am waiting for the day to come when we can do 3D printing on a micro and nano scale so then you go and create not only a form, but also the material properties and how it behaves … imagine foamy, spongy, gnarly materials… and somehow get graphene into the mix. This is going to get crazy.”(2)

There are endless possibilities to be explored; both digital and traditional will grow, mix, change and move into their own paths.

Susan Taing, director of 3D printing company bhold.co says “It’s like the food industry. For years people bought cheap chicken and beef and didn’t care where it came from. Then they got interested in locally grown food, and that started a movement. The same thing will happen with products—we’ll go back to a more artisanal market, with a lot of smaller local hubs, enabled by technology.”(3)

{food itself is another frontier. rice cereal was printed in the shapes of Janne Kyttanen’s signature pieces – heads, light fixtures, shoes, iphone covers, and his signature .}

So how will 3D printers fit into our lives in the future? There are several scenarios. Small 3D printers for the home are becoming more commonplace; although they are limited in their capabilities and the quality of their output, still, you can use your own software and create your own things. Or, you can contribute to sites such as Thingiverse (an offshoot company of Makerbot), which is like an opensource community – upload and share your designs.

At the other end of the spectrum are high end specialist printers that are capable of printing in various types of materials, where designers can send their files to be printed professionally. Companies like Shapeways work with architects, designers and more.

Certainly 3D printing is gaining in momentum. Will it extend to the point where there is a ‘copyshop’ in every suburb, so that locals can go and get anything they need? Car parts, new chairs, specialty tools for other DIY projects. Who knows?

While you’re about it, check out the 159 PAGES worth of 3D printed goods on Etsy – some are good, some are very, very bad, and some are, well, just meh. Just like any other craft.

How do YOU see 3D printing fitting into what you do – is there any possibility? Specialist tools for your traditional craft? Decorated accessories for your existing tools? New design ideas for jewellery? Or even a new coffee cup to drink from while you work? I would LOVE to hear from you especially if you already incorporate these technologies in your work.

Cheers! Julie X